Exactly 53 years ago this month a combined force of American and Vietnamese MPs and civilian police raided the “no-whites-allowed” area of Soul Alley in Saigon, a refuge for African American soldiers from the sometimes casual, often overt racism of their comrades-in-arms. A month earlier, a US Military Police Jeep had ventured in – its two occupants left without their guns and their vehicle, prompting the raid on this area that the US military authorities had conveniently chosen to ignore.

This is how Time Magazine reported the incident a few days later.

Time Magazine: Monday, Dec. 14, 1970

Just after the 1 a.m. curfew one day last week, 300 heavily armed American and Vietnamese MPs, civilian police and militiamen, supported by 100 armored cars, trucks and Jeeps, swooped down on a narrow dirt alley in Saigon and sealed it off.

As their house-to-house search began, G.I.s groggy with sleep and drugs scampered in every direction, a few over rooftops, trying to escape.

Their women followed, some stark naked, some wearing only pajama bottoms, as spotlights from two helicopters above played on the bizarre scene. When the roundup ended four hours later, 56 girls and 110 G.I.s, including 30 deserters, were hauled off into custody.

Known as Soul Alley, this 200-yd. back street is located just one mile from U.S. military headquarters for Viet Nam. At first glance, it is like any other Saigon alley: mama-sans peddle Winston cigarettes and Gillette Foam Shaves from pushcarts, and the bronzed, bony drivers of three-wheeled, cycles sip lukewarm beer at corner food stalls as children play tag near their feet.

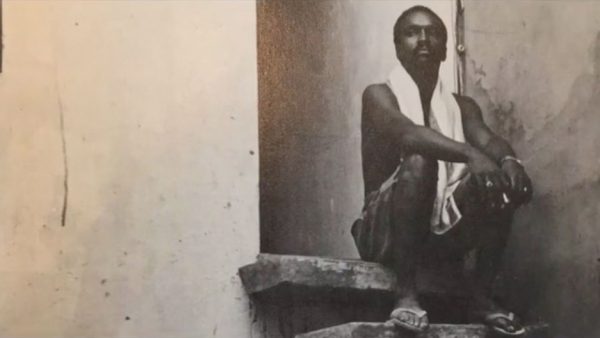

A closer look, however, shows that Soul Alley is a very special place. The children being bounced on their mothers’ hips have unmistakably Afro-Asian features. A sign in the local barbershop proclaims: THE NATURAL LOOK HAS ARRIVED. Green Army fatigues hang from balcony railings to dry in the sun. Black G.I.s talk and laugh, their arms around slight young Asian girls.

No Whites Allowed.

Soul Alley is home for somewhere between 300 and 500 black AWOLS and deserters. They escape arrest by using forged ID cards and mixing with the even greater number of G.I.s who are still on active duty but prefer spending nights here, away from the drabness of their barracks.

There were roughly 65,000 cases of AWOL last year, and the Army estimates that about 1,000 soldiers will become deserters this year (no racial breakdowns are available).

Whites who venture into Soul Alley do so at their own risk, as two military policemen learned a month ago. Five minutes after they drove in at mid-morning in their Jeep, they walked back out—minus the vehicle and their weapons.

The Army has known about Soul Alley and its deserters ever since the haven sprang up three years ago, and MPs have frequently staged minor raids and roundups. The incident with the Jeep sparked the biggest raid yet. But even if the brass cleaned up Soul Alley, its residents, rather like the Viet Cong, would soon drift back or relocate in another, similar spot.

Easy Living.

For many Soul Alley AWOLS, the living is easy. Explained one: “You get up late, you smoke a few joints, you get on your Honda and ride around to the PX, buy a few items you can sell on the black market, come back, blow some more grass, and that’s it for the day.”

Rent for the second floor of a brick house rarely runs to more than $40 or $50 a month, including laundry and housekeeping services. Hustling is the name of the game here. This gives everyone plenty of money for anything from soul food at a restaurant called Nam’s to hi-fi equipment, television sets or even heroin. Here is how the system works:

From an army of papa-san forgers, the AWOL gets his phony ID and ration cards. He goes to the PX, buys an expensive item, such as a refrigerator, for as little as $71.50 in military payment certificates (MFCS). On the open market, he can sell it for $500 in MFCS. Markups on TV sets and stereo sets are almost as high.

Special Signal.

Despite such amenities, life in Soul Alley can be lonely and miserable. Many of the AWOLs would rather be back home, but cannot leave Viet Nam without facing arrest and court-martial. Some would like to stay in Soul Alley, or something like it, but wonder whether they can.

“I don’t want to go back to the States, and certainly not back to Houston, Texas,” said a black G.I. who is married to a Vietnamese. “They would call me a ‘nigger’ and my wife a ‘gook,’ and they would never leave us alone. But I can’t get a civilian job here when I get out of the service.”

Besides, many have found that they jumped from one form of racism into another, since Vietnamese often do not like dark-skinned people. Add to this the harassment by MPs, the sense of being without a country, and the day-today hassle to raise money, and the frustrations can grow unbearable.

One G.I. summed it up: “It ain’t the rules; it’s the man. Same as back in the world. A black man is the only one they grab for spitting on the streets. Over here if a bunch of brothers get together to blow some grass, right away the officers get uptight; in the next barracks over, white guys are doing the same thing, but nobody bothers them.

“The regs [Army Regulations] say you can grow your hair this long, but the first sergeant says he don’t care what the regs say, because he don’t like no black man with a ‘Fro.”

This sort of feeling has given rise to a special variation of the intricate signal that black soldiers in Viet Nam exchange when they meet. The standard greeting includes two taps on the chest —meaning “I will die for you.” In Soul Alley, some blacks add a swift downward motion of the hand—a stroke to kill.